It would be a huge debate if one says migration has been a new phenomenon in Ghana as far as Ghanaians are concerned. From the early ’90s to date, many Ghanaian migrants could be spotted in neighboring countries like Nigeria, Côte D’Ivoire and Burkina Faso. In recent years, however, irregular migration—traveling without genuine documents and through unapproved routes—from Sub-Saharan Africa and possibly Europe has increasingly gained grounds.

But is it not hugely surprising that in 2018, Ghana was ranked fifth by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) as the country with the most illegal migrants to Libya with a whopping 31,251 populace. Does this not point out clearly that there are a hand full of people who have already migrated and others still migrating to this north African country persistently? Living in a country with relatively little lucrative jobs for its youth; the fear to be tagged as lazy and the pressures to provide for themselves and their families alone are adequate grounds to preparing the minds of many in considering the Libya trip a priority. The mentations of most youth nowadays come in two folds; the calamities traveling might cause and the prospective benefits that could be gained.

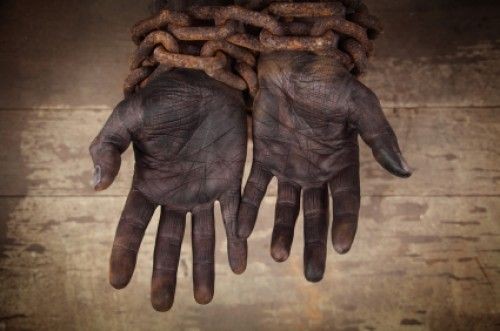

Although many are aware of how unsafe the travel to make ends meet might be, they are just not perturbed so far as its benefits will follow. Motivated by the popular saying “the best view comes after the hardest climb”, the typical Ghanaian youth will do everything within his or her prowess to be victorious. As if the motivation to illegally migrate to Libya does not end there. The untold truth by veterans of this precarious journey seems to make the situation much more complicated.

These “Libyan Borgas” could somehow be partly apportioned blame as they build up the confidence of prospective travelers to embark on such a risky voyage as if it were a mandatory religious pilgrim. Though it would be difficult to dig out the main reasons as to why these veterans do not reveal the whole truth about brutalities they had once faced, one thing certain is that they would not want their highly reputable “Libyan Borga” title to be underplayed and tempered with.

As to whether the journey is seen as a precarious venture or a perfect opportunity to triumph, the undeniable fact that still lingers is, a substantial number of youth are left with little or no choice than to undertake the dangerous voyage as many crave for prosperity. Is this not how the idea of going to Libya builds up? Is this not how it all begins?